Interdistrict open enrollment programs allow students to attend public schools outside of the district where they reside. Forty-three states have these programs, and hundreds of thousands of students take advantage of them each year, making them among the most widespread school choice programs in the country.

Although interdistrict open enrollment programs are designed to provide families with public school options beyond the district where they live, the design of these programs often limits the set of choices that families can select. The most common problem stems from provisions permitting districts to reject transfers from out-of-district if their schools lack capacity to serve additional students. These provisions are well-intentioned—policymakers do not want open enrollment programs to pose an undue burden for capacity-constrained districts—but they can create challenges for families looking to enroll their children in a nearby district. It is difficult for families to know which districts may have the capacity to educate their children.

To assist Oklahoma’s families in navigating the interdistrict transfer process, the state legislature passed Senate Bill 783 in 2021, which was subsequently signed into law by Governor Stitt. The law requires each Oklahoma district to post available capacity in each grade level at every school in an easily accessible place on the district’s website. To ensure that families had up-to-date information on potential transfer options, the statute also requires districts to update these capacity postings on a quarterly basis. Policymakers deemed these updates important since the law widened the transfer window and let families enroll in a new district at any point during the school year.

Although Senate Bill 783 required districts to post available capacity regularly, it did not directly provide districts with resources to help them comply with this mandate, and the statutory language was vague about potential sanctions for districts that did not comply. Together, these considerations raise the possibility of districts disregarding the mandate to make grade-level capacity publicly available on their websites.

To investigate this issue, my colleague Noah Wolff and I conducted a research project that involved visiting the websites of all 500+ Oklahoma school districts and systematically recording district compliance with the capacity-posting requirements of Senate Bill 783. However, it quickly became clear that some districts had defined capacity as the number of seats in each grade for every school, with no attention to the number of those seats actually open to would-be transfer students.

Our data collection process distinguished districts that only posted capacity (i.e., the total number of seats) and those that also posted availability (i.e., the number of seats that potential transfer students could occupy). For districts posting capacity or availability, we recorded whether the posting met Senate Bill 783’s requirement that the information be updated on a quarterly basis. Finally, we logged the number of clicks it took to access the capacity information from the district’s homepage.

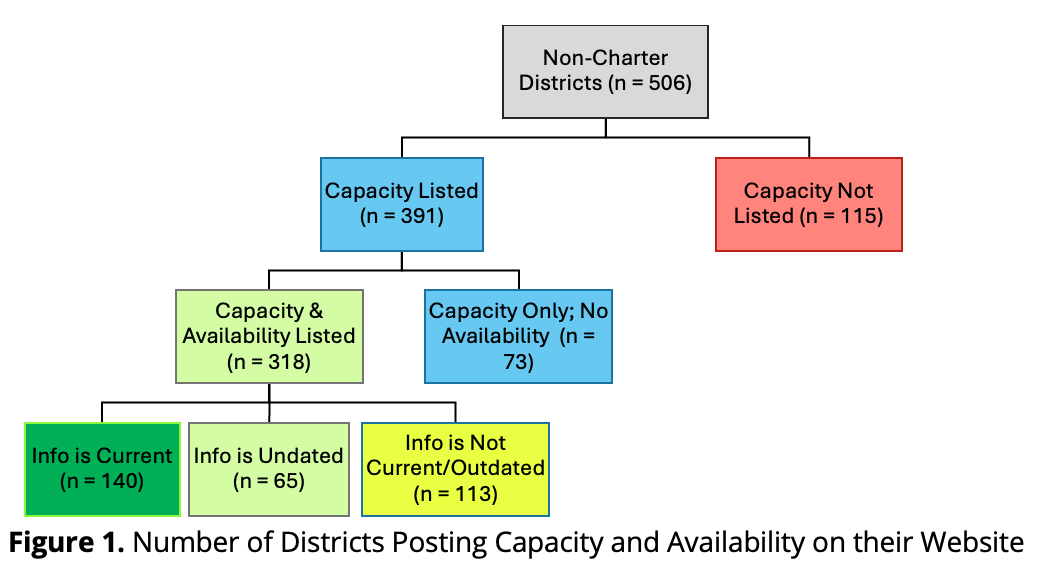

Our results indicate that 140 out of 506 Oklahoma districts—about 28 percent—fully complied with the requirements of Senate Bill 783 by posting the number of currently available seats in each grade in every school that potential transfer students could occupy. On the flip side, 115 districts (approximately 23 percent) had no information about capacity on their website. In other words, districts that are either fully compliant or entirely noncompliant account for about half of Oklahoma’s districts. The other half are partially compliant.

Figure 1 provides details on the different forms and frequency of partial compliance. The figure begins by illustrating that 115 districts had no capacity posting on their website, but the remaining 391—accounting for more than about three-quarters of districts—had some form of capacity posting. Of these 391 districts, 73 districts had only posted capacity, with no attention to the availability of any of those seats to potential transfers. This means that 318 districts, about 60 percent of all districts in the state, had both capacity and availability posted on their website. However, about one-third of those postings (n=113) were demonstrably outdated and an additional 65 districts had no date listed, making it impossible to determine whether the information was up to date. The remaining 140 districts had information on capacity and availability that was clearly current.

Senate Bill 783 requires districts to post available capacity in a “prominent” place on the district website. And there were a handful of districts that heeded this mandate by posting it directly on their homepage. These districts were a small minority though, and our data indicate that it took two clicks from the home page to access capacity information for the median district. On one district’s site, six clicks were necessary to reach the information. While most districts with capacity postings made the information viewable directly on the website, there were 21 districts that made users download a document—usually either a Word document or a PDF—to see available capacity.

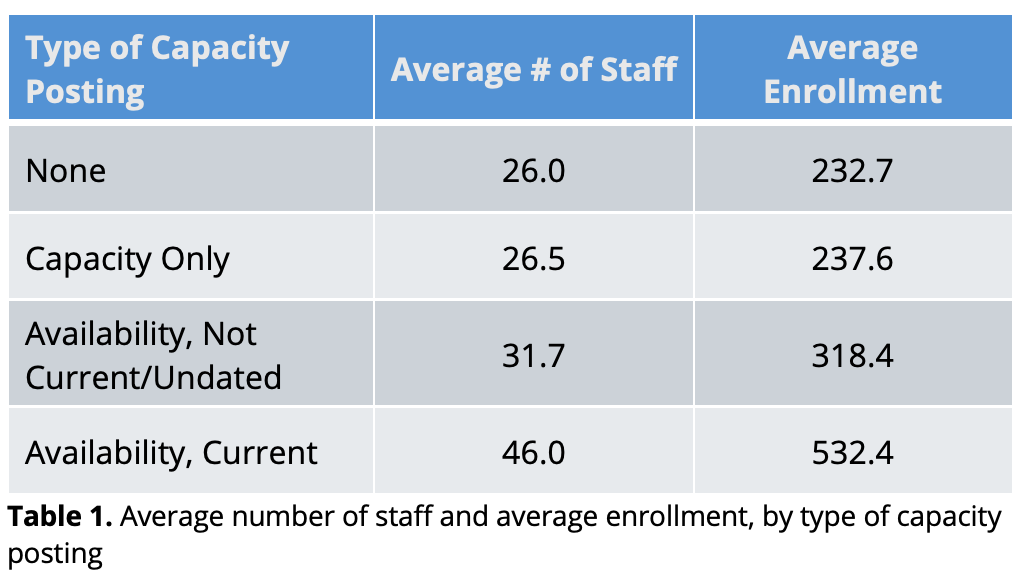

The patterns depicted in Table 1 are striking but perhaps unsurprising. Districts with verifiably current seat availability posted to their website enroll more than twice as many students and have nearly twice as many staff as districts that either post nothing or only list capacity, with no information on seat availability. Districts with outdated information on seat availability had about five more staff members on average and approximately 80 more students than districts without any information on seat availability, but these numbers still lag far behind districts with up-to-date information. Although not definitive, our findings suggest that at least some portion of noncompliance may be attributable to a lack of capacity (pun intended) among district personnel—recall that Senate Bill 783 did not provide districts with any additional resources to support collection and publication of seat availability.

The provisions of Senate Bill 783 requiring districts to post available capacity in each grade level at every school on an easily accessible place on the district’s website were developed with the best of intentions—they were designed to help families navigate the complex interdistrict transfer process. However, with legislation offering neither resources nor sanctions, it is unsurprising that our project found a nontrivial share of districts were out of compliance. And it is even less surprising that this noncompliance is disproportionately concentrated among districts with relatively fewer staff. Going forward, Oklahoma’s policymakers would do well to continue working to provide families with the information necessary to assess their schooling options, but they might also need to consider ways to help districts produce that information.

We also used data from the National Center for Education Statistics’ Common Core of Data to calculate the average number of district staff members and the average district enrollment for four categories of districts: 1) Those that had no form of capacity posting on their website, 2) Those that posted capacity only with no information on actual availability, 3) Those that posted availability but the information was either undated or outdated, and 4) Those that posted verifiably current seat availability on their website.

Suggested Citation. Carlson, D. (2024). Open Doors or Roadblocks? Assessing District Compliance with Oklahoma’s Student Transfer Laws. Oklahoma Education Journal, 2(3), 13-17.