Between 1866 and 1976, Black Americans claimed more than 650,000 acres from the U.S. government through the 1862 Homestead Act. Kalenda Eaton, Ph.D., associate professor in the Clara Luper Department of African and African American Studies, Dodge Family College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Oklahoma, and director of Oklahoma Research for the Black Homesteader Project, is working to recover, reevaluate and reclaim the histories of rural African Americans in the Oklahoma Territory pre-statehood and beyond.

“The National Black Homesteader Project wanted a separate focus on Oklahoma due to its unique history,” Eaton said. “Regarding Black history, we have Indian Territory, Oklahoma Territory, as well as a very large population of people of African descent who moved into Oklahoma. The descendants of those who were already here, and those who came later, remain a part of the Oklahoma fabric today.”

Research shows that more than 8,000 people of African descent were living in the Indian Territory prior to the land runs, primarily as enslaved members of Native tribes. After emancipation and as a result of changes to the land allotments after 1865, homesteads in the Indian Territory were allotted to emancipated Black Indian freedmen.

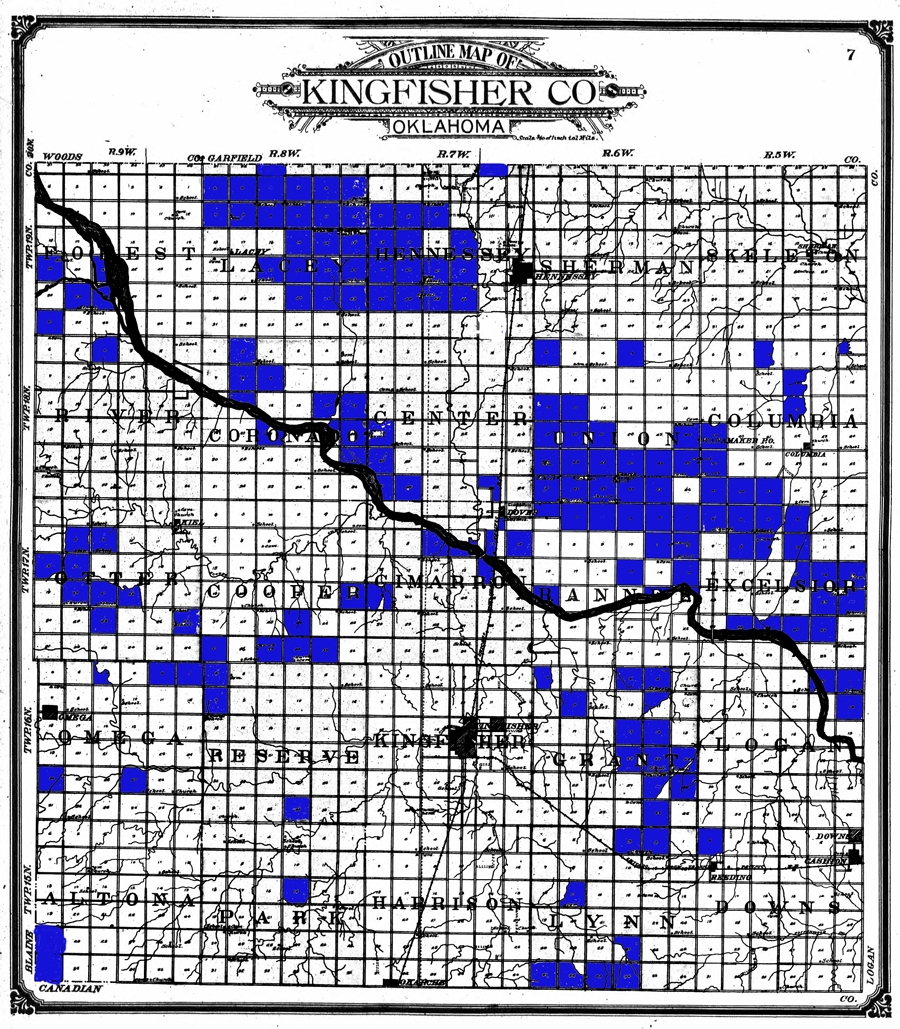

“Due to the rich and complex history of Oklahoma, we have limited the geographic area of the Black Homesteader Project to the western portion of the state – known as the Oklahoma Territory. This is where the bulk of claims were filed under the Homestead Act,” Eaton said. “We see this project as an opportunity to highlight counties, communities and people who might otherwise be overlooked in our state and national history.”