“We have this spent fuel, it’s already there. We can’t wish it away, and it has to go someplace safe, but the way that these projects were being approached by government agencies and the engineers from the national labs and so forth was almost designed to generate conflict,” Jenkins-Smith said. “The engineers came up with what they thought was an optimal design by assuring safety and keeping costs down. They would approach a community and say, ‘We’d like to put this here,’ and because of the imagery of nuclear issues and radiation and so forth, that evoked an almost knee-jerk anti-siting response.”

Instead, the research team – which includes nuclear engineers, physical scientists and social scientists – has adopted a “community-first approach,” Gupta said. Their project will simulate the process of how to engage a community in the design and construction of a nuclear waste storage facility.

“Part of the problem with previous efforts was that the community was brought in a little too late, so we decided the first phase is going to be community elicitation before anything else,” Gupta said. “We would essentially start with a blank slate, asking the community when thinking about such a facility what are the types of things that come to their mind to try to elicit some of their wishes and needs and vision for such a facility for their community long-term.”

Project collaborators from the Center for Socially Engaged Design at the University of Michigan are helping develop the community engagement assessments. Starting first with a one- to two-day workshop, the researchers will develop tactics to recruit participation in a listening session as well as the questions and mechanisms that could be used to gauge community sentiment. Those “local” data points would then be paired with a national survey to draw out broader themes and gauge public views at both a local and national scale.

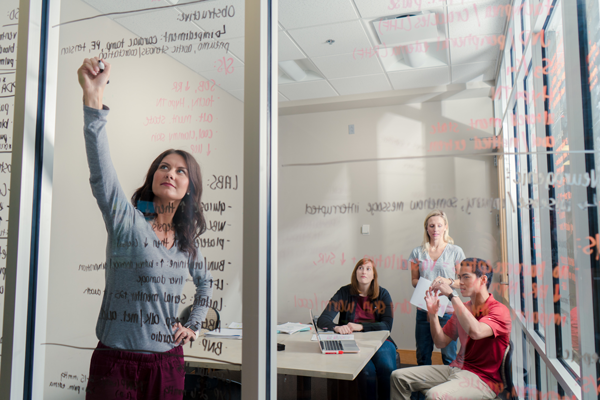

“We would take the responses from the community and bring that to engineers and scientists in phases two and three of the project to get them to think about ‘here's what the community wants, now how do we work with this?’” Gupta said. “I think what is truly innovative about this project is that we are flipping that process, going into the community first and then having the scientists grapple with community requests at the outset … then the final phase is bringing them together for a co-design – bringing them together in the same room to come up with broad features of a facility that matches the vision of the community, but also the physical and scientific attributes that the facility needs to have.”