Trails to Indian country define Oklahoma

By Addison Kliewer, Miranda Mahmud, Sarah Beth Guevara

Gaylord News

WASHINGTON—The Trail of Tears, the forced removal of the Cherokee Nation to Oklahoma, was one of the most inhumane policy implementations in American history––but it was not an isolated incident.

Nearly 16,000 members of the Cherokee Nation were forced under armed guard in 1831 to leave their native homeland in the southeastern United States to trek more than a thousand miles to what would eventually become the state of Oklahoma.

Almost 4,000 Cherokees died along the way, never making it to the land designated by the U.S. government as Indian Territory.

Removal of the Choctaw Nation commenced even earlier, in 1830. Like the Cherokees, they left behind their homes and a way of life developed over millennia to start over in an alien environment on the prairie.

But the Cherokee and Choctaw nations are only two of the tribes with a removal story. There are 39 tribes in Oklahoma, five native to the state, that have stories to be told––each with its own Trail of Tears.

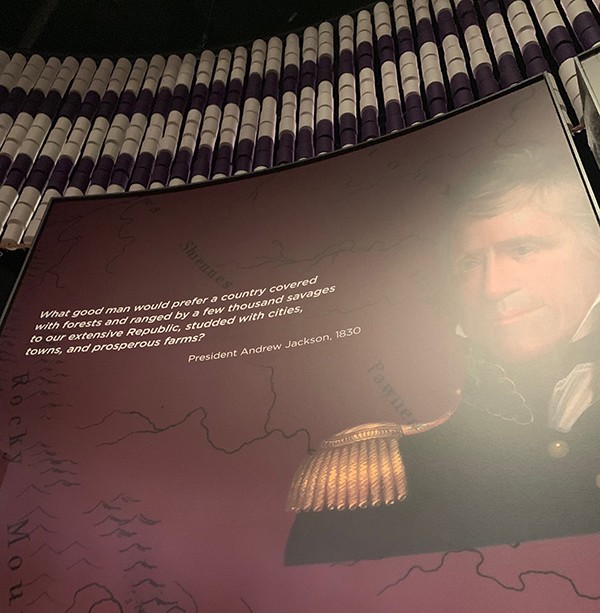

Long before the removal period, the federal government believed white people could use the Native lands better than the original inhabitants. This “Indian problem” motivated settlers to strip Native people of their land and resources, constantly pushing tribal members farther west.

That pressure often resulted in militant ambushes toward Native Americans from settlers. If the Indians fought back, it was only proof to whites that they were savages.

While the Constitution established sovereign Indian nations with treaty rights, removing tribes from the Southeast was a growing idea by the time Andrew Jackson was elected president in 1828. He became one of the most forceful advocates after proposing the Indian Removal Act as one of his first pieces of legislation.

Jackson believed that moving the tribes west of the Mississippi River was essential to national security and he had no qualms about violating existing treaties, according to Jackson biographer Jon Meacham.

“The Southern states were anxious for more land, especially to grow cotton, and the Creek, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw and Seminole tribes held rich acreage––great chunks of which would become modern-day Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi and Tennessee,” Meacham wrote.

Appeals from the tribes that they held the land by treaty fell on deaf ears in Washington. Jackson simply did not believe the Indians had title to the land, and he would not tolerate competing sovereignties in the United States.

Opponents of the act said removal was immoral and illegal, but it was approved in 1830 by a wide margin in the U.S. Senate.

The act passed by only four votes in the House and set 1838 as the date for final removal––the year after Jackson left the White House. To those who argued for Indian rights, Jackson argued that removal would guarantee the survival of the tribes.

Instead, removal launched an era of genocide.

In 1835, the Jackson administration signed the Treaty of New Echota, supposedly with the Cherokee Nation in Georgia, setting terms for the final removal of the tribe west of the Mississippi River.

The treaty had been signed by a small group of Cherokees who did not represent the majority of tribal members. But Jackson insisted they did.

“The people who signed removal treaties were not actually representative of public sentiment in their nations. That is why such a large number of Indians refused the treaties, to the point of hiding out rather than be rounded up by the government for forced removal,” said Barbara Mann, who holds a doctorate in English language and literature and has written several books about the Indian Removal Act.

The federal government dispatched thousands of troops to enforce the ill-negotiated treaties.

“The philanthropist will rejoice that the remnant of that ill-fated race has been at length placed beyond the reach of injury or oppression, and that the paternal care of the General Government will hereafter watch over them and protect them,” Jackson said in his farewell address to the nation.

Rather than protecting the tribes, the military was brutal, and one-fourth of the Cherokees died along the trail from disease, starvation, exhaustion and exposure.

“I fought through the Civil War and have seen men shot to pieces and slaughtered by the thousands, but the Cherokee removal was the cruelest work I ever knew,” Meacham quoted one Georgia volunteer as saying years later about the removal.

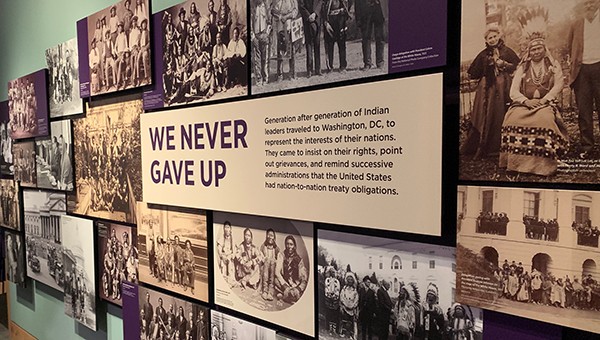

The typical American history book treats the Trail of Tears as an isolated incident, said Kevin Gover, director of the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian and former assistant secretary for Indian Affairs in the U.S. Department of the Interior.

“But in fact, that was the policy of the United States for the better part of 100 years, to remove Indians from their homelands and then sell the land that Indians left behind to non-Indian settlers,” said Gover, who is Pawnee and grew up in Oklahoma.

Removal was not solely the result of Andrew Jackson behaving in bad faith, Gover said. He said it was a national project.

“It was something the United States decided to do, and they did it,” he said. “It's essential in the telling of the story, in order to make it palatable to Americans today, to say, ‘Well, there weren't that many Indians, and they were, after all, savages. They weren't really using the land, and so it was OK.’”

Mann said removal in the first place was “one big, immoral, unethical illegality.”

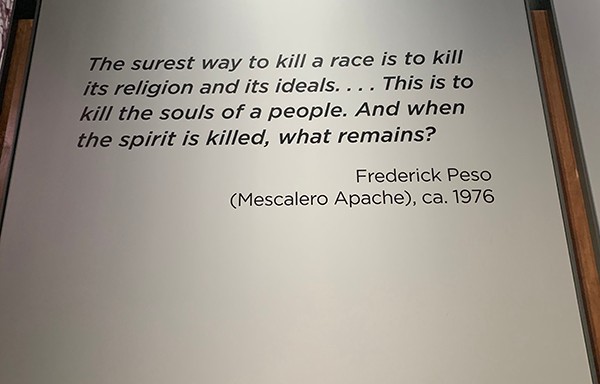

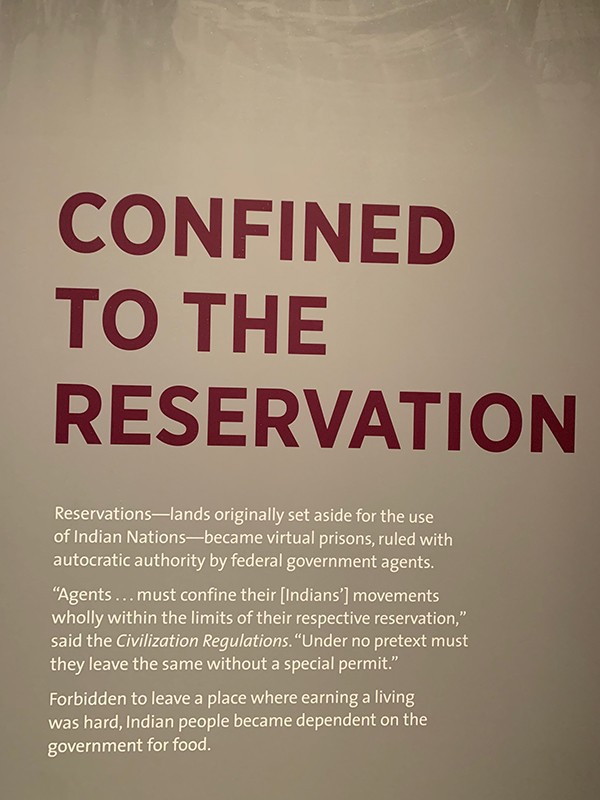

The wrongdoings of the federal government did not end after the removal period. The government continued for many years to strip Oklahoma tribes of their land and culture.

The Dawes Severalty Act of 1887 was intended to assimilate Native Americans into white society by stripping them of their cultural and social traditions.

The act allowed the federal government to further divide tribal land and granted citizenship only to those who were willing to accept the division.

For tribes in Oklahoma, the removal stories have not been forgotten.

“None of the tribes I know want to live in the past,” said Rep. Tom Cole (R-OK), a member of the Chickasaw Nation. “But the best way to make sure the mistakes of the past are not repeated is to remember them and make sure it never occurs again.”

As a child, Cole said, he never saw his grandmother carry a $20 bill, which flaunts the face of Andrew Jackson.

“I didn’t even know who Andrew Jackson was, but I knew he was a bad man,” Cole said.

Cole is one of four Native Americans in the U.S. House, along with by Rep. Markwayne Mullin (R-OK), Rep. Deb Haaland (D-N.M.) and Rep. Sharice Davids (D-KS).

The ramifications of the Trail of Tears persist today, observers say.

Tribes are constantly battling to protect their land, their people, the environment and their water rights, Gover said. Additionally, tribes address challenges that many communities in the United States face such as opioid addiction, family dysfunction and abuse, he said.

Because the United States never kept many of the promises made in the treaties, Mann said, “Every nation in the East was the victim of the same predator.”

The Trail of Tears still has open wounds, making it necessary for treaties to continue to be litigated 180 years later.

The Cherokee Nation is still working to uphold provisions of the Treaty of New Echota, the removal treaty that guaranteed the tribe the right to a representative in Congress.

“I don't think that it serves anyone's interest to forget the shared history that we have––the black chapter that we have––because we know that Native Americans have experienced plenty of those,” said Kimberly Teehee, who the tribe has named as its delegate-designee for that long-promised seat in Congress.

A case now before the Supreme Court, Carpenter v. Murphy, could undercut the tribes’ legal jurisdiction in Oklahoma, as well as legally disestablish reservation boundaries.

“I would be nervous, were I out in Oklahoma,” said Mann about the case.

Next year will mark the 50th anniversary of President Richard Nixon’s speech advocating for Indian self-determination.

“They kept taking and taking and taking. It was only in the 1970s that the tribes really began to reverse all of that,” Gover said. “We've been in what we call a self-determination era, only for the last 50 years.”

Despite these challenges, tribes are responsible for much of the economic growth in the state, especially in rural communities, Cole said.

Oklahoma tribes had a $12.9 billion impact on the state’s economy in 2017, making them one of the top economic drivers, according to a study on Oklahoma Native Impact.

“Oklahoma tribes support 96,177 jobs in the state, representing $4.6 billion in wages and benefits to Oklahoma workers. While direct employment exceeds 50,000 jobs, tribal investment spurs job growth in many different industries,” the report said.

If Native communities were to leave Oklahoma, Gover said, many non-Indians who depend on the tribes would suffer.

To understand the accomplishments and cultures of tribal nations today requires understanding the merciless removal period, he said.

“The only thing I'm confident about is that the Indians will never give up,” Gover said, “and they will never stop being Indians.”