Otoe-Missouria Tribe

By Katelin Hudson

Billie Ann Tohee, an Otoe-Missouria tribal member and Iowa tribe descendant, recognizes the unequal opportunities that surfaced once the Europeans forced their way onto Native soil.

“Thomas Jefferson (said) ‘all men are by nature equally free and independent,’ which might’ve been true, except he wasn’t talking about the Otoe-Missouria - or any other tribe for that matter - he was talking about the white man,” Tohee said.

Tohee is not alone in identifying this injustice.

In 1955, the Otoe-Missouria tribe sued the federal government on the grounds of not being paid the fair market value for the Big Blue Reservation, a plot of land in Nebraska they felt forced to sell in 1881.

They won $1.2 million.

Born the same year the case went to court, Tohee grew up witnessing the Otoe-Missouria taking back their identity, but she was also raised on the teachings of her mother, who was born in 1915 and remembered seeing her people assimilate to survive.

“We had to assimilate until we lost aspects of our culture; we had to assimilate until we lost our language; we had to assimilate until we lost our identity,” Tohee said. “My mother never forgot that.”

The Otoe-Missouria was originally two distinct tribes: the Otoes and Missourias. Both originated within the Great Lakes region and eventually migrated into what are now the states of Nebraska, Iowa, Kansas and Missouri. The earliest record of the tribes’ specific location was on a French map in 1673.

The tribes dominated the land and the Missouri River that passed through it.

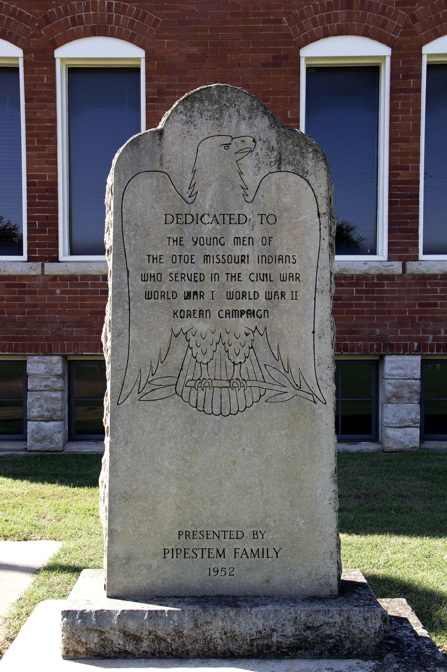

They were the first to have government-to-government council with the newly created United States, trading with the French and Spanish for hundreds of years prior. Additionally, were the first tribes to hold council with Lewis and Clark.

Heather Payne, public affairs officer, said disease and intertribal warfare ultimately diminished tribal numbers and forced the Missouria to seek help from the Otoe.

The Otoe-Missouria stayed on the Big Blue Reservation until they refused to suffer any longer under the Office of Indian Affairs, which pressured the tribe to relocate. The tribe sold the reservation and used the money to buy a plot in Indian Territory.

In October 5, 1881, a procession of 320 Otoe-Missouria tribal members walked 18 days to get to Red Rock, Okla.

The only thing standing at that time was a building used by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Payne says.

While the building has a diverse history of being used as a stable, jail, police department and as a storage shed, now the Otoe-Missouria use it as a language center to revive their dying language: Jiwere-Nut’achi.

Today, the Otoe-Missouria are maintaining the parts of their culture they were able to hold on to.

“While we’ve lost pieces of our culture in the past, I think the best thing we can do is move forward and hang on to what little we got,” Tohee said. “We’ve got to cherish and continue our traditions.”

Katelin Hudson is a reporter with Gaylord News, a reporting project of the University of Oklahoma Gaylord College of Journalism and Mass Communication.