Kickapoo Tribe

By JaNae Williams

Through numerous accounts, one thread of Kickapoo history remains: forced movement. It was something the tribe saw so frequently, and in such a manner, that their origin cannot be connected to one distinct location.

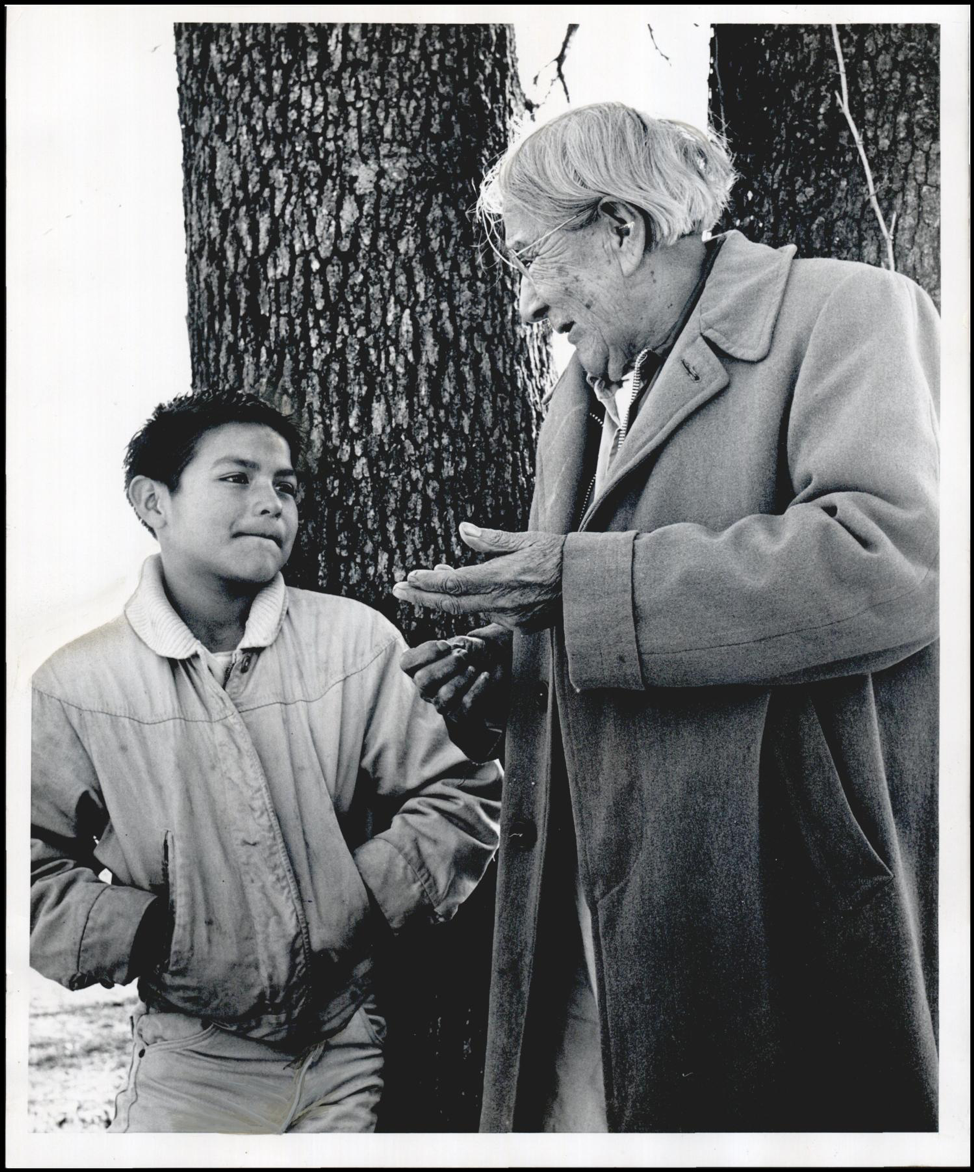

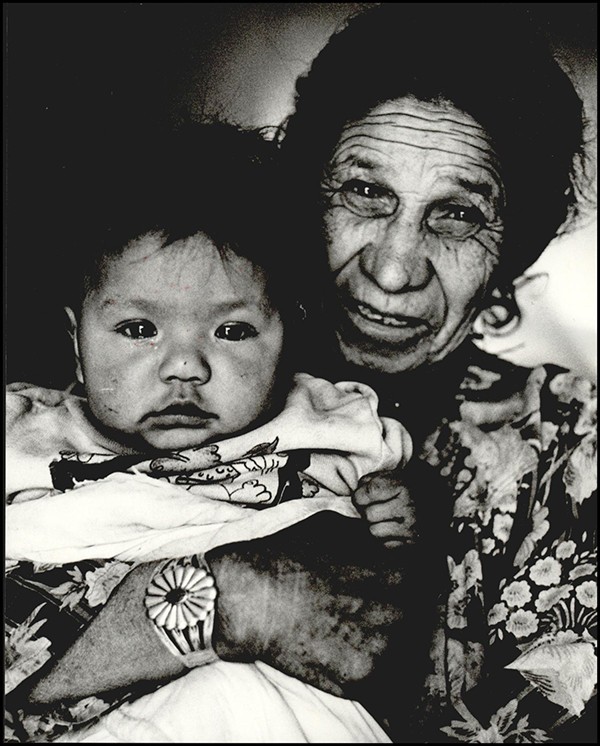

“I used to hear [the elders] talk about how the Army made them move over again, [but the settlement] wasn’t there very long until we had to move again,” recalled Cecelia Pensoneau Blanchard, the first female chairman of the Kickapoo Tribe, in a 1985 interview with Joe L. Todd, archived by the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Blanchard was born in February 1909, just west of McLoud on her father’s allotment. Her father, Steve Pensoneau, was Kickapoo and Potawatomi, but mostly Shawnee as she remembers it. His allotment was one of few Shawnee tracts that fell north, rather than south, of the Canadian River.

Axie Lunt, or Pem-meah-quah, as she was known in Kickapoo, was her mother. Lunt died when Blanchard was 7, leaving her to a life in Indian boarding schools and helping to raise her younger siblings.

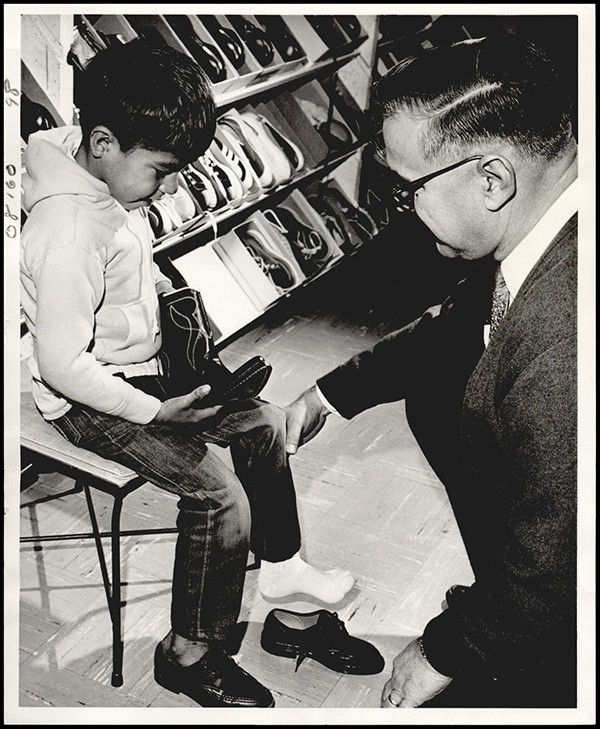

She began her education in McLoud, but soon went to Shawnee Mission School and eventually found herself at Shawnee Indian School, a facility run by the Bureau of Indian Affairs that she describes as more like an orphanage.

“We had to wait on tables and clean our dormitories, and [we would] get demerits if we talked Indian, and that’s one reason why I don’t talk Indian,” Blanchard said. “I was doing a pretty good job of it when my mother was living, but after she left I had no one, you know, immediately around me, talking.”

Her mother was a member of what Blanchard caled the Ohio Valley band of Kansas Kickapoo Indians.

“The place they talked about most was Wabash up in Illinois,” Blanchard said of her mother and the other older Kickpaoo telling of their journey to Oklahoma. Historical records of the Kickapoo people often link them to the Great Lakes region. The tribe split after leaving Wisconsin and the Prairie band stayed in central Illinois, while the Vermilion band occupied the Wabash drainage of which the elders spoke.

Both the Prairie and the Vermilion bands, the latter of whom the Mascouten joined, signed treaties with the United States in 1819 giving up the rights to their land.The bands would ebb and flow, moving into various areas of the country, eventually settling in Kansas, Mexico, Texas and Oklahoma, before the Civil War.

The portion of the Kickapoo Tribe that lived in Texas would face contention due to the newly independent country’s anti-Indian policies. Eventually this led to many of the Texas and Mexican Kickapoo moving into Oklahoma, then southern Kansas, where they would join the Union, raiding those tribes in Oklahoma that fought with the South in the Civil War.

The Civil War was not the only time Kickapoo joined the war effort. During World War I, while Blanchard was at Haskell Indian School, the U.S. Army convinced many of the young men they would be better off serving the country than staying in school, she said in the recorded interview.

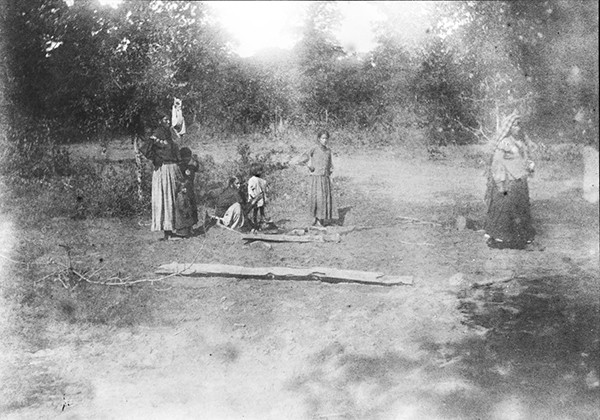

After the Civil War, the Kickapoo were three main groups: Kansas, Oklahoma and Mexican, according to the “Handbook of North American Indians.” The Oklahoma Kickapoo at this time lived in an area between the Canadian and Deep Fork Rivers. This area would eventually become the site of the final Oklahoma land run in 1895.

From 1890 to 1893, the Oklahoma Kickapoo divergence into two groups became distinct. The traditional group opposed allotments and the culture of settlers, and the progressive group embraced modernity. Federal officials were eventually able to gain signatures of tribal leaders on documents agreeing to allotments and in 1893 many settlers, or Sooners, began moving into Kickapoo Territory, years before the official opening May 23, 1895.

The land run on Kickapoo Country remains one of the most contentious points of history for the tribe and many Oklahomans. The area involved a small amount of land, and promises to remove Sooners and grant land to those settlers who had waited went unfulfilled.

The Kickapoo are an Algonquian-speaking people closely related to the Sauk and Fox and Mascouten tribes. Native lore holds that the Kickapoo and Shawnee tribes were once united, but disbanded due to a disagreement concerning the foot of a bear. Several other tribes have affiliations with the Kickapoo in history, including the Miami, Potawatomi and Quapaw.

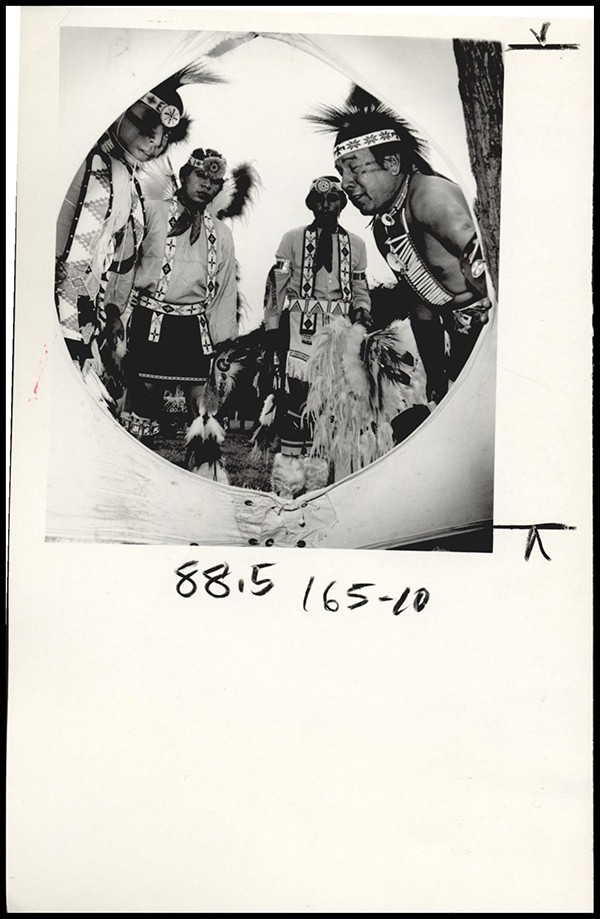

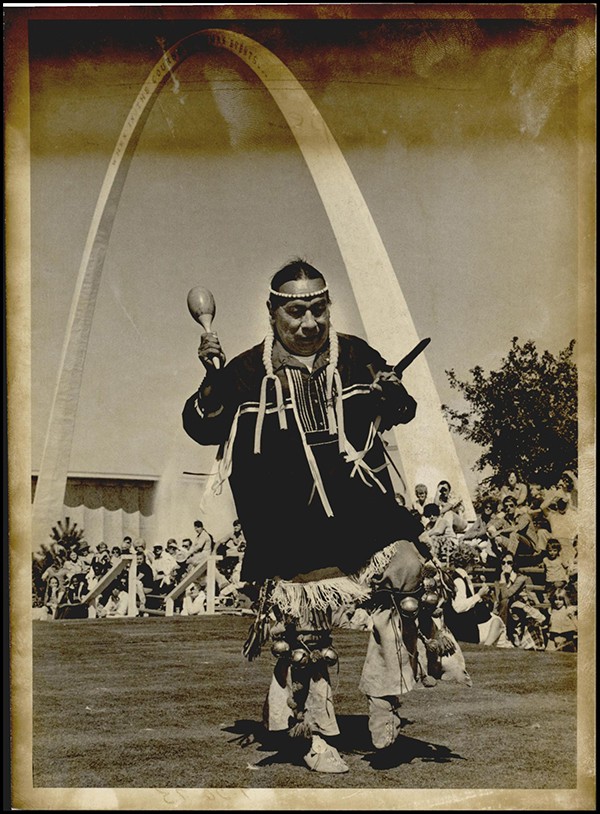

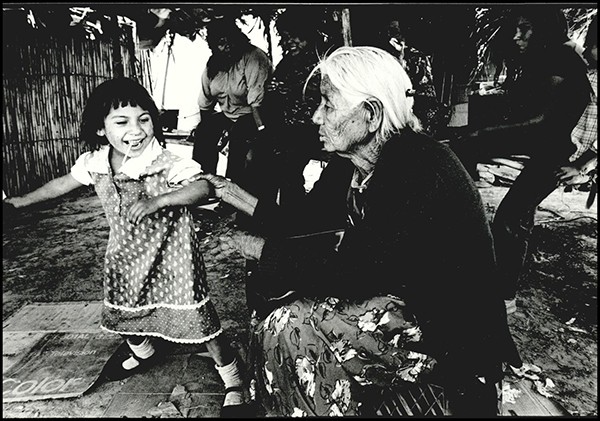

Blanchard remembered in the interview that during powwows each tribe would have a story about the origin of life, each one staking some claim on creation. She said Native Americans have been coexisting and exchanging goods and services since long before anyone thought to keep a record.

“That exchange has been the strength [of the Indian],” Blanchard said. “They say the Indian is diminishing, but they’re really not because [of] where intermarriage and a lot of other things have kept them.”

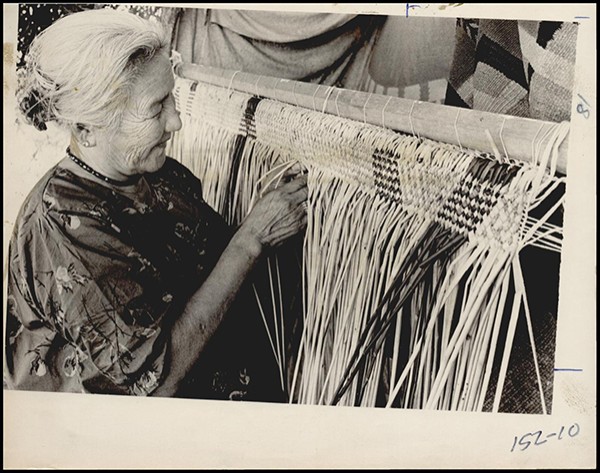

At the time of the interview in 1985, Blanchard had a collection of items including a dress she’d been gifted from the Blackfoot Tribe and a buffalo drum. Most of her artifacts had come to her from other tribes and she hoped they would someday end up in a museum.

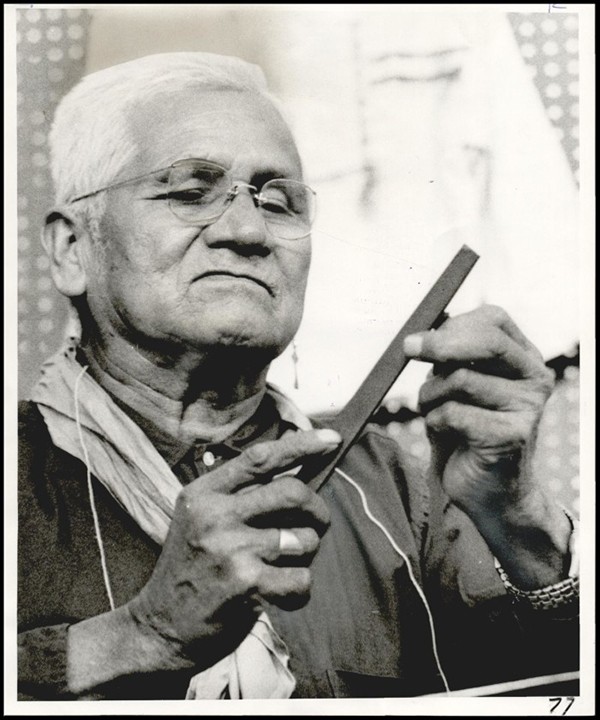

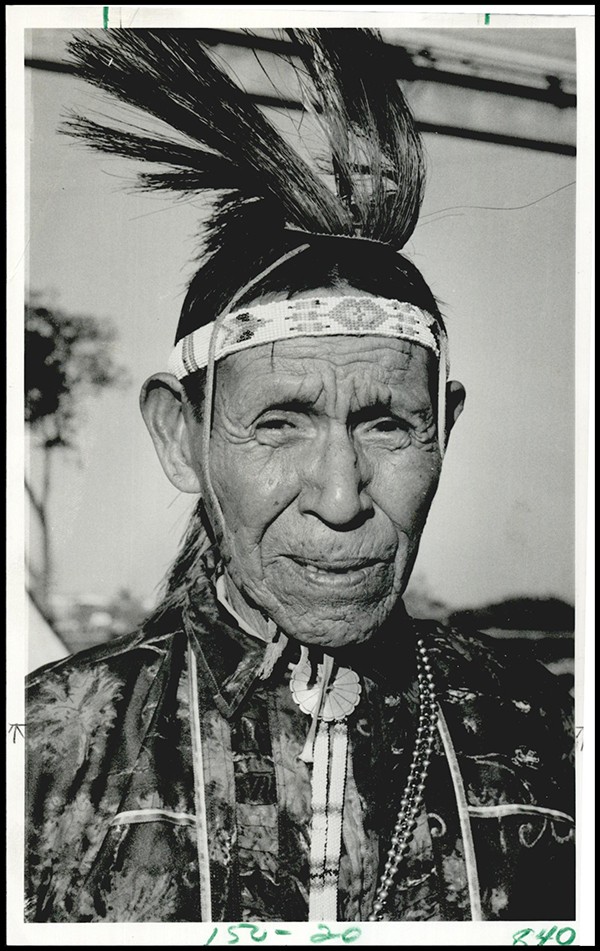

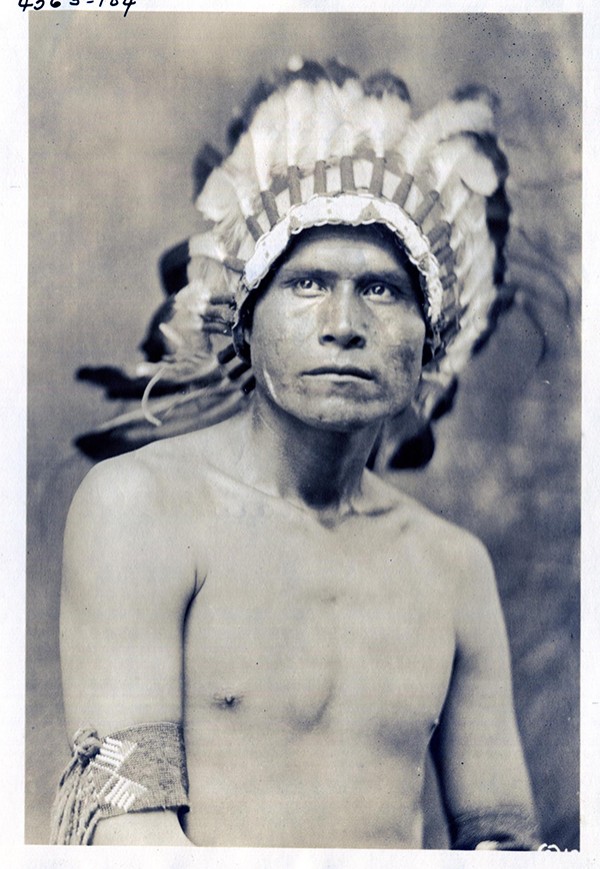

Throughout her interview, there were moments when Blanchard would come to subjects that she felt were not hers to fully speak about, despite her once high standing in the tribe. When asked about Kickapoo headdresses, she mentioned that some parts of the topic were sacred but shared what she was able to.

“There’s a high respect for [eagle] feathers, I can say that, and when you see a lady wearing a feather, it isn’t right,” Blanchard said. “It’s supposed to be up there and not on her. Kickapoo ladies respect the feather.”

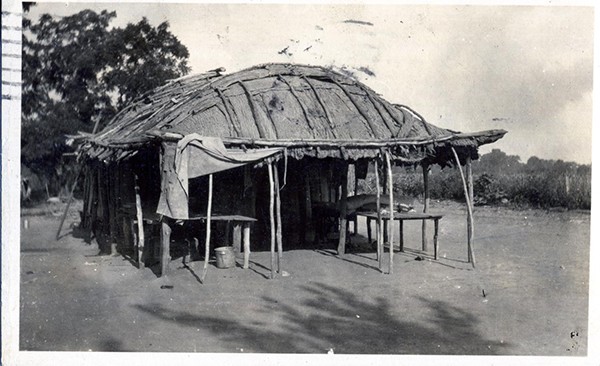

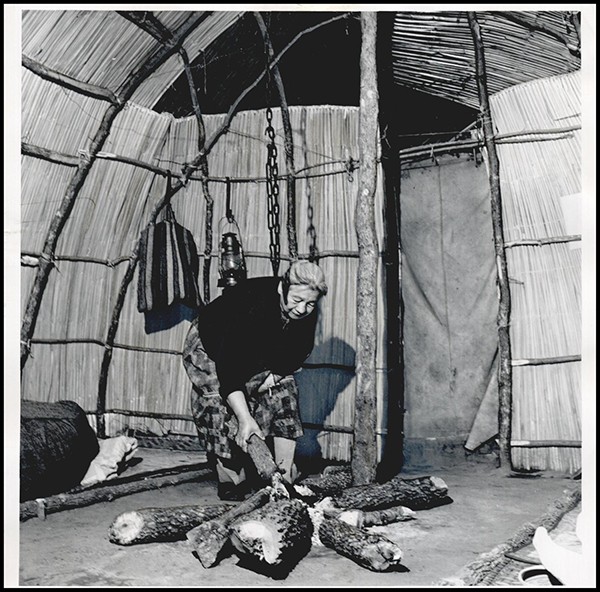

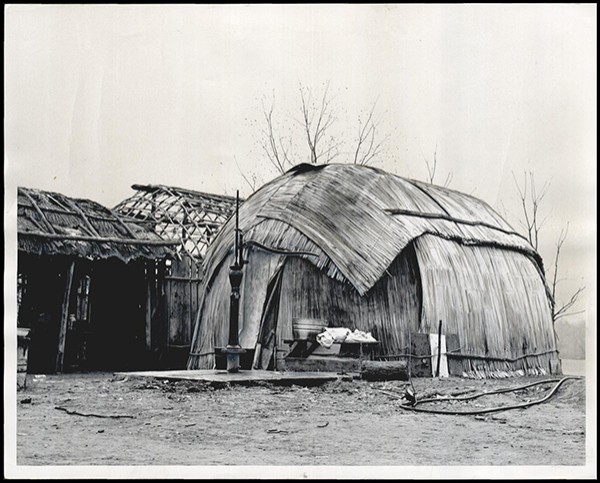

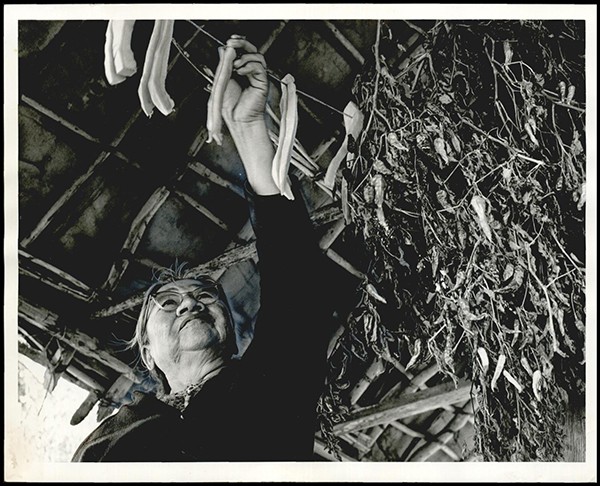

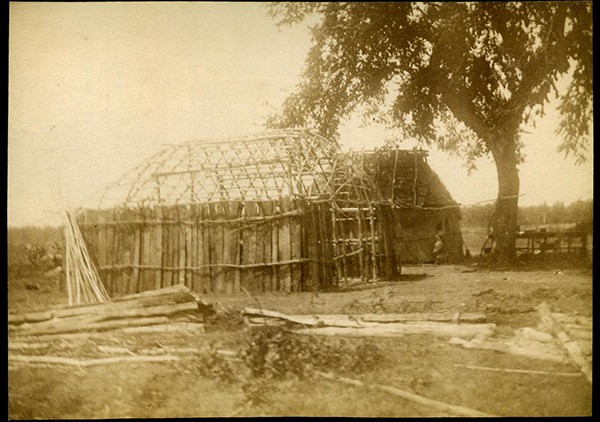

Blanchard explained that the reason some things are not discussed is because they were viewed as sacred or beneficial and considered to be where strength comes from by many Native American tribes. This can range from naming ceremonies to the very dwellings Native Americans inhabit.

“It’s like a cathedral. Maybe your family wouldn’t be entitled to one, but I could come there and enjoy and partake of it,” Blanchard said.

The Kickapoo Tribe of Oklahoma’s history is rich and complex. Though, according to Blanchard, looking forward with your fellow human in mind was the most important thing for all tribes.

“Now these are the types of things that I think are detrimental to Indians, not just Kickapoo, but to Indians: lack of foresight,” Blanchard said. “It may not do me any good, ‘So what?’ There’s people out there that are more important than I ever thought of being.”

Janae Williams is a reporter for the Vista, the student newspaper at the University of Central Oklahoma.