2018 marks the 25th anniversary of the first excavation at the Cooper Folsom bison kill site in northwest Oklahoma. Cooper’s claim to fame includes the discovery of a painted bison skull (the oldest painted object in North America); three separate, stratified, large-scale kill episodes in a single arroyo; and exquisite examples of Folsom projectile points made from a variety of chert sources hailing from as far north as northcentral Kansas and as far south as central Texas.

25 Years of Cooper: Folsom Bison Hunting and Beyond

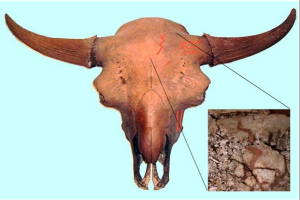

Painted Bison Skull Discovered at the Cooper Site

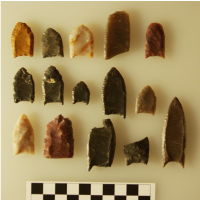

Lithic Tools discovered at the Cooper Site

The distinctive Folsom projectile point, with its sleek lanceolate design, exquisite often minute flaking, and distinctive long channel flakes that extend from the base to the tip, dates to between 10,900 and 10,200 radiocarbon years ago and marks one of the earliest cultures known in the New World. The preceding Clovis culture used larger spear points to hunt mammoths and other large late Pleistocene game. Folsom replaced Clovis and, with the extinction of the late Pleistocene megafauna, turned to hunting the massive bison.

In juxtaposition to the large-scale kills are small-scale kills of usually one or a few bison alongside pooled water. Sites include the Lubbock Lake site near Lubbock, Texas and the Waugh site near Buffalo, Oklahoma where a small group of bison were ambushed during the winter along a bend of an unnamed spring-fed stream. These sites often have the bones of one or two bison piled together after the meat was removed and are thought to be the handy-work of a single family of hunters. Other animals besides bison were also hunted and trapped. As one might expect, Folsom groups collected a wide variety of animal and plant resources; but evidence of these resources is not well preserved in the archaeological record.

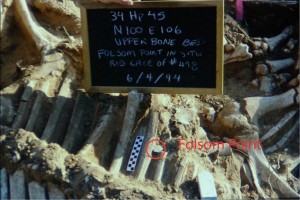

Folsom Point pictured in situ at Cooper Site

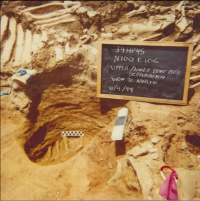

Since the initial excavation in 1993 the Cooper site has figured prominently in over 40 publications ranging in scope from professional peer reviewed articles and book chapters, including one book, to popular publication in a children’s magazine. The lithic assemblages contain points and flake knives made of Edwards Plateau chert, Alibates chert, Niobrara jasper, Dakota quartzite, and silicified wood. The bison (Bison antiquus) assemblages contain predominantly cow and calf groups numbering at least 20, 29, and 29 animals in each of the three episodes, (lower, middle, and upper kills, respectively).

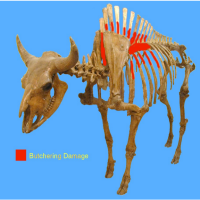

Diagram of Butchered Faunal Remains at Cooper Site

These minimum numbers represent an estimated 1/4th to ½ the number of individuals in each kill episode: the rest having been eroded away by the Beaver River channel over the course of some 10,500 radiocarbon years. Each kill occurred during the late summer/early fall of the year. Butchery of these animals targeted the highly prized cuts of the hump, shoulders, and tenderloins. This selective style of butchering suggests the hunters were mainly after the prime cuts of meat to provision large numbers of people gathered nearby for other activities, perhaps including dancing, feasting, and socializing associated with annual or at least cyclical aggregations or rendezvous. Although the idea of large group get-togethers had been pondered for Paleoindian times, the archaeological evidence for these aggregations were not readily evident for Folsom times and definitely not expected to be represented in bison kill sites. The possibility that hunting groups from different portions of the Plains came together to socialize and feast on bison gave rise to the Cooper model of Folsom hunting adaptations.

Similar large-scale late summer/early fall Folsom bison kills were known at the Lipscomb site along Wolf Creek in the northeast corner of the Texas panhandle and at Lake Theo located further south in the Texas panhandle where a possible shrine consisting of a bison skull placed atop a pedestal of upright mandibles had been unearthed. With the re-analysis of the Folsom type site in northeast New Mexico, yet another example joined the ranks of large-scale arroyo trap bison kills, this one seasonally slightly later in the fall. And finally, in 2010, the Badger Hole late summer Folsom arroyo trap bison kill was found only 700 meters upstream from Cooper. Badger Hole paralleled Cooper in many ways, including the selective pattern of butchery that targeted the hump and shoulders.

In addition to recreating their subsistence practices, we know Folsom flintknappers had a penchant for high quality, colorful cherts to make their distinctive projectile points. The sequence for manufacturing a Folsom point has been reconstructed by studying the flaking debris left at lithic quarries and camps, and by studying the Folsom points themselves. Given all that has been discovered, there is still debate exactly how the distinctive channel flakes were removed. Several different techniques could have been employed, including free-hand soft-hammer percussion, indirect percussion using a punch, or levering the channel flake by use of a pressure flaking fulcrum system. All three techniques replicate the finished Folsom points found at sites. So perhaps all three techniques were used at the discretion of the flintknapper.

There is still much that we don’t know about Folsom people, their technology, and subsistence. We do not know what Folsom people looked like or if they buried their dead. The recovery of eyed bone needles indicates they made tailored clothing, a must to combat the cold weather and conditions of the Younger Dryas climate. They probably had dogs, but evidence for dogs is scarce. We also have hints of the types of structures they may have built during cold weather, including roughly circular stone foundations probably covered with hide. But when all the evidence is combined, we have only a sketch of their lives, technology, and subsistence. Each new site promises a better understanding of these people and their culture and a better insight into the diversity of adaptations people develop to handle everyday situations and demands.

If you are interested in learning more about the Cooper Site you can purchase the book published by our own Dr. Leland Bement.