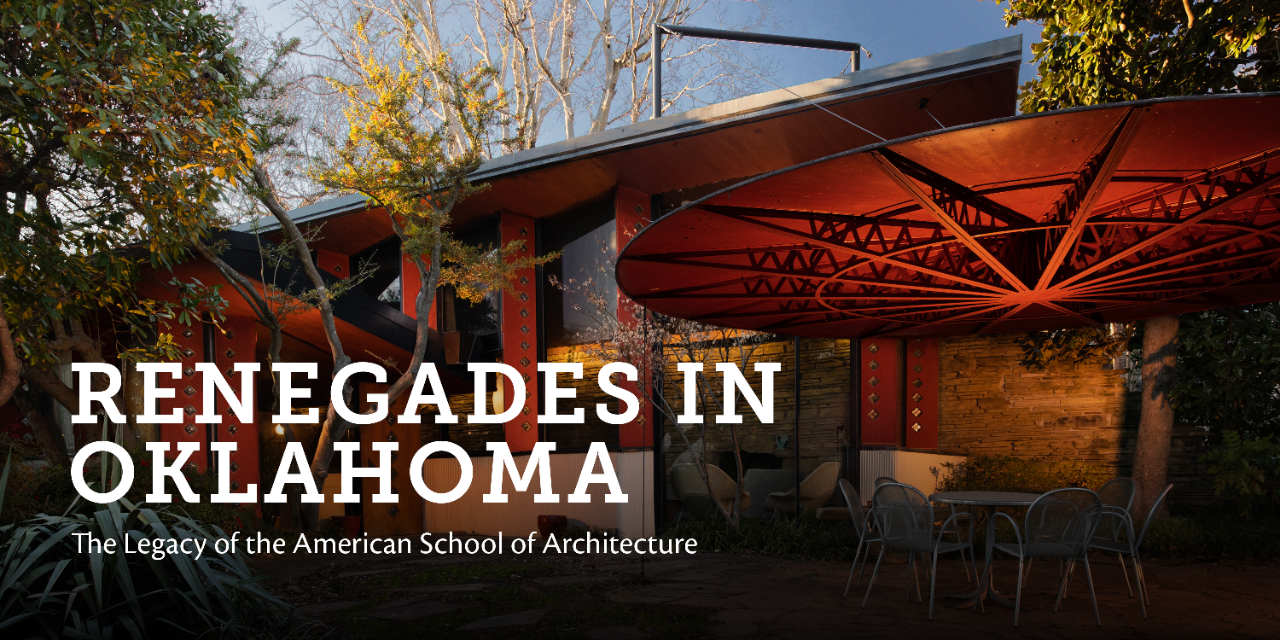

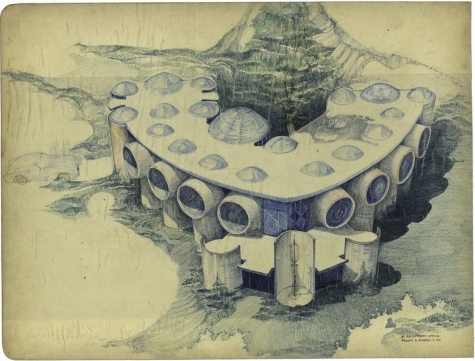

A large display hangs from a wall in the Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art showcasing student architectural concepts from various schools across the United States in 1957. Most are familiar renderings of idealized structures comprised of straight, pragmatic lines converging to create beautifully simple, yet sophisticated concepts. One among them however seems to stand in defiance of the others with organic, free flowing shapes creating structures with a painterly quality. This is the work of the American School.

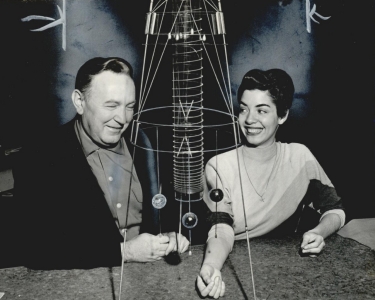

Bruce Goff, who served as the chairman of the School of Architecture at the University of Oklahoma from 1943-1955, had already departed from the program by this time. Yet, his influence was evident; the school had gained national acclaim during his tenure, receiving recognition from publications such as Architectural Forum and Life Magazine as one of the best architecture schools in the United States.

Aspiring architecture students flocked from across the nation to Oklahoma to attend the program and learn under the tutelage of Goff and some of the other brightest minds in architecture.

But what made this school unique in a field brimming with talent across the post-war globe? The answer to this question – hidden in the its very name – is paramount in understanding the American School’s legacy.