A Collaborative Approach

There are five primary science teams working on this project, each comprised of researchers from across the state. Each science team is responsible for identifying a group of peer scientists who will evaluate the teams’ work.

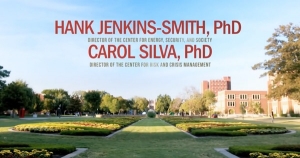

Silva and Jenkins-Smith lead the social framework team which is working to establish a process for integrating the perspectives of the science teams with a panel of approximately 100 state opinion leaders, as well as a random sample of statewide households in order to identify promising solutions in the overlapping areas being investigated by the science teams. An annual “academy” will bring scientists, opinion leaders, and representatives of the public together to discuss the research progress and provide an opportunity to collaborate on innovative solutions to Oklahoma’s most pressing land use, water availability, and infrastructure problems.

“We view this as an iterative process in which the science teams are presenting what they’re learning to decision makers and the public. At the same time the scientists are going to learn about ways to work with these groups and take into account their ideas, preferences, and concerns,” Jenkins-Smith said.

One of the research teams will focus on how Oklahoma’s seasonal and subseasonal weather patterns are likely to shift over time and what those implications might be. Another will address terrestrial water and carbon dynamics as they relate to climate change and land management. A third will investigate water reuse and sustainability. The fourth team will study the infrastructure implications for these topics.

Jenkins-Smith said there are two downstream implications to changing weather patterns. One has to do with the availability of water, “Oklahoma is going to have to deal with a world in which an increasing fraction of available water is going to be of marginal quality, meaning substandard water for some uses, and highly variable – through overabundance during pluvial (flooding) events and drought.”

“These seasonal and subseasonal weather pattern shifts are going to dramatically impact agricultural use,” Jenkins-Smith said. “It’s going to affect the degree to which plant matter grows and our susceptibility to wildfire dangers, which may be a growing issue for us over time. Included in both the marginal quality water and the carbon surface area management are such things as the produced water from oil and gas developed with hydrologic fracking. We get a lot of produced water during this process, and we need to figure out appropriate treatments that could make produced water more useful in more contexts.”

The other implication from changing weather patterns is the topic of land surface area management, as well as storing and managing carbon.

These issues also intersect with our infrastructure. Jenkins-Smith added. “We have an infrastructure system that is both directly and indirectly affected by seasonal and subseasonal weather patterns, changing patterns of land use management, impacts of wildfires, or drought-caused subsurface instabilities when aquifers decline.”

While these problems intersect all of these domains, they are also subject to diverse concerns and perceptions.

Jenkins-Smith offers the example of climate change. “Climate change is perceived very differently by different subsections of the population. We get a pattern of growing problems of great complexity overlapping into multiple areas for which potential solutions are bogged down by polarization within our population and political system. This project aims to break that cycle by taking advantage of the overlapping array of problems to find solutions that can be both innovative and acceptable by very different populations, making it possible to come to agreements over these shared challenges.”

One way in which this project might produce a sustainable solution would be in leveraging the state’s expertise in the oil and gas industry.