Check out the most recent edition of the Energy Institute newsletter!

On the role and significance of OPEC’s spare capacity

For many years, analysts have viewed oil market stability in terms of the excess production capacity maintained by OPEC. Recently, shale oil supply may have overshadowed the role of OPEC spare capacity in the minds of some market analysts. However, with oil prices currently surpassing $70 per barrel, accompanied by increased geopolitical uncertainty and diminished upstream investment, OPEC’s spare production capacity is back on the global market agenda.

I recently coauthored a paper[1] with Axel Pierru and Tamim Zamrik (both from KAPSARC, Riyadh), “OPEC’s impact on oil price volatility: The role of spare capacity.” Published in The Energy Journal in March 2018, this paper is part of an ongoing KAPSARC research program focused on the opportunity cost of oil.

Part of OPEC’s statutory mission is to “ensure the stabilization of oil markets.” The purpose of our research is to shed light on the factors that have influenced OPEC’s calculation of the volume of spare capacity to achieve this part of its mission and to estimate the extent to which OPEC’s utilization of spare capacity has stabilized the price of crude oil. To our knowledge, our paper is the first attempt to fit a structural model to the behavior of OPEC’s spare capacity in pursuit of these questions.

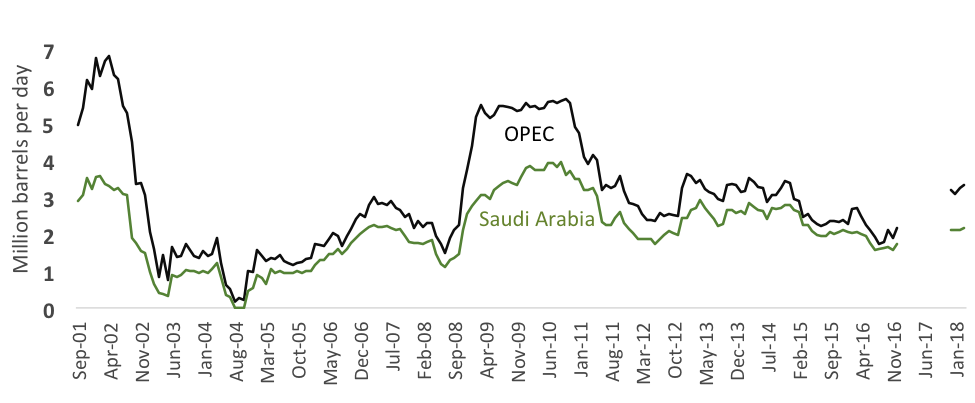

Figure 1 shows the change in monthly “effective” spare capacity reported by the International Energy Agency (IEA) since 2001. OPEC’s effective spare capacity amounted to 3.2 million barrels per day in June 2018, with world oil demand forecast to reach 100 million barrels per day by the end of the year. Saudi Arabia has held, on average, 70% of OPEC’s spare capacity since 2001.

Figure 1. Effective spare capacity (source: IEA’s Oil Market Reports). IEA does not report data from January to November 2017.

We use existing monthly data to build and estimate a model according to which OPEC maintains a buffer of spare capacity to offset shocks to global oil demand and supply. We assume that OPEC sets a target price (we are agnostic on what that is and how it has varied through time) and manages spare capacity to reduce volatility around the target price. This involves withholding production when the price goes below the target (which increases spare capacity) and increasing production when the price exceeds the target. We assume that these attempts are subject to error, due to misperceptions about the size of the shock and administrative and logistical constraints on production adjustments, which limit OPEC’s ability to stabilize the price of oil.

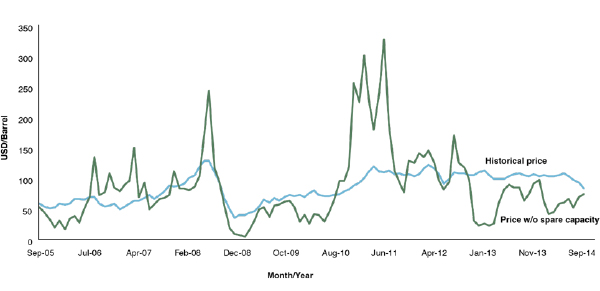

Based on our model and the historical data, we can estimate a counterfactual monthly oil price that assumes that OPEC did not use its spare capacity to offset shocks. The counterfactual price shown in Figure 2 can be compared to the historically observed price, but this requires an assumption regarding the short-run elasticity of demand. In constructing the counterfactual price, we have assumed the monthly price elasticity to be -1%, which is plausible. But because no one can say exactly how price-responsive global oil demand is, Figure 2 is an approximation of the impact that OPEC’s spare capacity has had. It is worth noting that, in the counterfactual, we assume that OPEC adhered to the same target price, so the average price is the same over our time interval for both the factual and counterfactual situations. The analysis we develop in the paper indicates that OPEC had a substantial stabilizing influence, perhaps reducing oil price volatility by as much as half. The analysis also shows that Saudi Arabia has absorbed more shocks than all other OPEC members.

Figure 2. Spare capacity reduces oil price volatility.

Note: Price with no spare capacity assumes -1% monthly price elasticity for global demand.

We also address the question: “Has OPEC maintained a volume of spare capacity sufficient to avoid the potential costs associated with oil price volatility?” Although historical spare capacity has never fallen to zero, this might be simply because the world was lucky and the shocks that occurred were mild. To estimate the size of the buffer that OPEC needs to achieve its mission of stabilizing prices, we must consider all possible shocks and their respective likelihoods. The study shows that the value of an additional barrel of spare capacity depends on the magnitude and persistence of the shocks, the existing buffer size, and the economic losses incurred when and if the buffer is insufficient to avoid production shortfalls. By applying the principle of revealed preference to OPEC’s observed behavior, we are able to infer the magnitude of economic losses that OPEC seems to have considered when making decisions about spare capacity. We compare this result to an independent estimate of global GDP losses due to oil supply disruptions (derived from the well-known Oxford Economics world macroeconomic model) and find that both values are consistent. This indicates that the size of OPEC’s buffer, estimated at 2.64 million barrels per day (1.94 million barrels per day for Saudi Arabia), has been in line with global macroeconomic needs. Furthermore, additional calculations show that the expected value of global GDP losses avoided by OPEC’s buffer could range between $170 and $200 billion per year.

In terms of neutralizing the impact of oil shocks, spare capacity is only one piece of a much larger picture. The recent emergence of shale oil as the world’s marginal producer has made non-OPEC supply more reactive to price, which also contributes to price stabilization, along with consumer inventories, strategic government stocks, and the very active hedging programs of oil producers and consumers exposed to oil price volatility.

[1]Vol 39(2), 173-196. Our paper is open access and can be freely downloaded from The Energy Journal’s website.