Each year more than 8,000 people die while waiting to receive a kidney transplant, many of whom have spent four or more years on donor waitlists, hoping for a miracle to arrive. These deaths occur due to a worldwide shortage of kidneys for transplantation because there is currently no reliable means to quickly and efficiently determine the viability of enough donor kidneys to meet the demand.

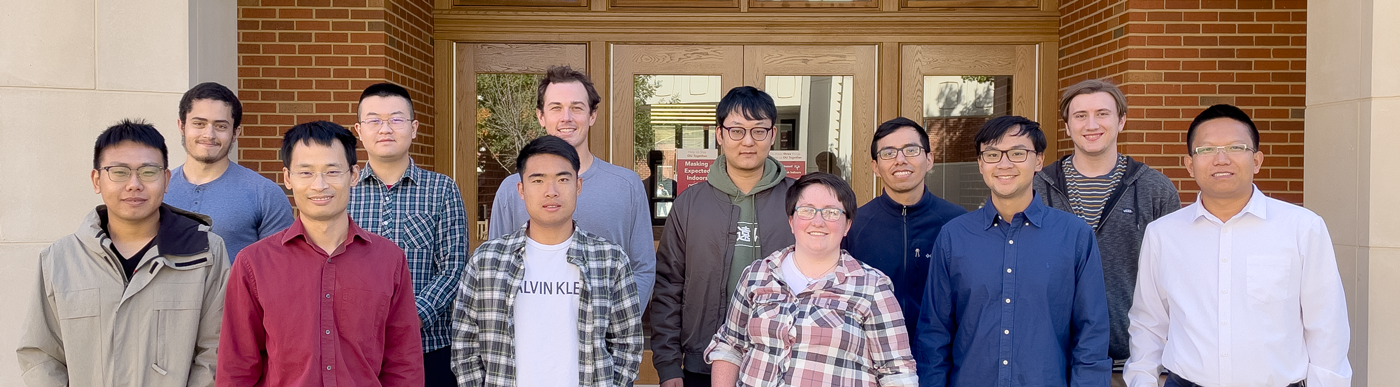

A team of researchers from the University of Oklahoma and the OU Health Sciences Center, with assistance from LifeShare of Oklahoma, as well as researchers and clinicians from the University of Massachusetts Amherst, Worchester Polytechnic Institute and Georgetown Medical Center will collaborate to investigate the use of optical coherence tomography to evaluate donor kidneys and develop new scanning methods and machine learning algorithms to reduce the evaluation time of donor kidneys while substantially increasing the information about the viability of these organs for transplant surgeons and clinicians.

Qinggong Tang, Ph.D., assistant professor at the OU Stephenson School of Biomedical Engineering, Gallogly College of Engineering, is the OU lead for the four-year study, funded by a $2.5 million National Institutes of Health R01 grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

“Our goal is to develop a better, more objective method for evaluating kidney quality than is offered by current methods,” Tang said. “We want to get more kidneys in the hands of transplant surgeons and make better use of the donor kidney pool.”

The current process for screening donor kidneys uses two methods – pathological scores based on anatomical features from a biopsy and the Kidney Donor Profile Index (KDPI) derived from the donor’s medical history. However, clinical research indicates that those current methods have limited discriminative power.

“By scanning the whole kidney surface, our device intends to eliminate the uncertainty created by the biopsy/KDPI paradigm,” Tang said.

In addition to Tang, the OU research team includes Chongle Pan, Ph.D., associate professor of computer science and microbiology; Kar-Ming A. Fung, M.D., Ph.D., professor of neuropathology and surgical pathology, director of neuropathology and director of electron microscopy at OUHSC; and Zhongxin Yu, M.D., a board-certified pathologist with OUHSC.

When assessing donor organs for transplant, Tang said there are two golden standards, pre-transplant biopsy score results and post-transplant clinical outcomes. Tang and his team believe that optical coherence tomography scanning technology can aid in predicting both.

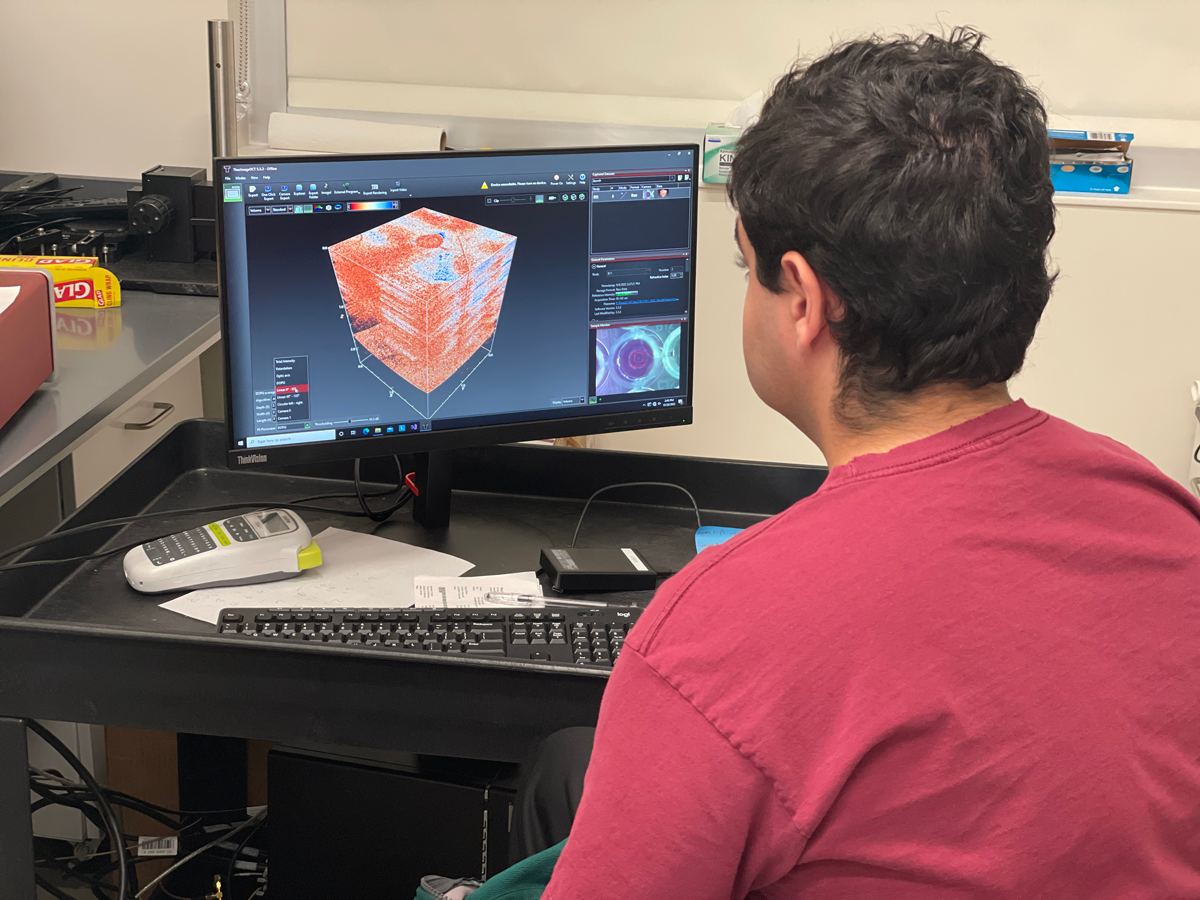

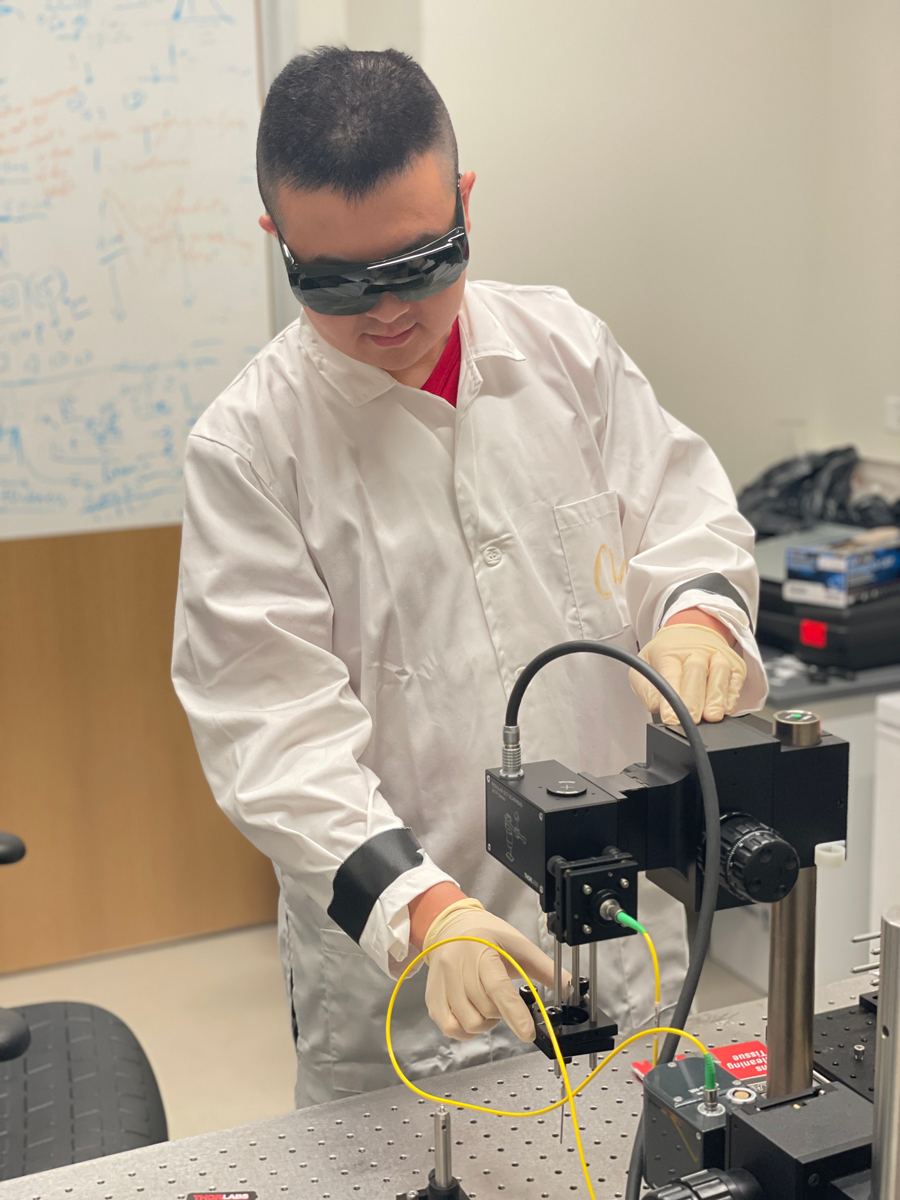

OCT is a non-invasive imaging test that uses light waves to take cross-section pictures of tissue, providing what is effectively an ‘optical ultrasound’ by imaging reflections from within tissue to provide cross-sectional images. The key benefits of OCT are the acquisition of live, sub-surface images at near-microscopic resolution with instant, direct imaging of tissue morphology without the need for preparation of or contact with a tissue sample.

“What we want to do is to automate the evaluation process,” Pan said, “so the data coming from the OCT device can be directly analyzed by machine learning algorithms and output a score that is comparable to the score surgeons are currently using. The surgeon can look at this score and determine if this kidney is right for their patient.”

Currently, pathologists often use a biopsy to assess kidney health which only provides information about the specific spot the biopsy is taken from. Since OCT is non-invasive, it is possible to scan the whole kidney and get a more complete view of the organ’s overall functional capacity.

“A kidney is a three-dimensional object. (Whereas) a biopsy can only assess one specific spot in that kidney to determine transplant viability, OCT scans can image about 1-2 millimeters below the surface of biological tissue,” Tang said. “For transplanting kidneys, this is very good because it is the most representative area of kidney functionality. By scanning the whole organ instead of taking a biopsy from a single area, the transplant surgeon can assess the spatial distribution of the function of the kidney and decide if it is a good match for their patient.”

OU researchers will be responsible for acquiring, scanning and obtaining an initial histological analysis of the kidneys, as well as developing OCT scanning and machine learning components. LifeShare of Oklahoma will provide 200 donor kidneys over the next four years. These kidneys will be scanned by Tang’s team and OU pathologists will provide the histology results.

Kidneys deemed to be viable for transplant will be added to the United Network for Organ Sharing system, the only organ procurement and transplantation network in the U.S.

The research team will observe the clinical outcomes of patients receiving these kidneys post-transplant, and OCT images of the kidneys will be correlated with post-transplant renal function to establish imaging algorithms and guidelines for OCT imaging of kidneys prior to their transplant.

For kidneys deemed non-viable by current pathological standards, the project will combine the biopsy results with OCT images to build a database and correlate the OCT image with the histology result, with the goal of verifying that the OCT images align with the histology results from the biopsies.

This combined pool of data will allow the team to develop deep-learning-based image processing algorithms to quantitatively assess parameters observed in OCT scans as indicators of the functional status of kidneys. As part of the project, they will also develop a robot-assisted automatic 3D scanning OCT device to image human kidneys prior to their transplantation.

Pan explained the diagnostic criteria developed for machine learning during this project will be based on the same scoring sheet clinicians are already using, except the sheet would be reproduced using OCT data rather than pathology slides.

“Right now, 40% of donor kidneys are discarded as being unfit for transplant,” he said. “By our estimate, of that 40%, there are a substantial amount that are actually usable. We are hoping to decrease the number of discarded kidneys to 25% and save more people’s lives.”

As a follow-up to this study, Tang hopes to use the same technology to develop OCT scanning protocols to aid in lung and liver transplants, as well as other tissues.

by Michael Mahaffey