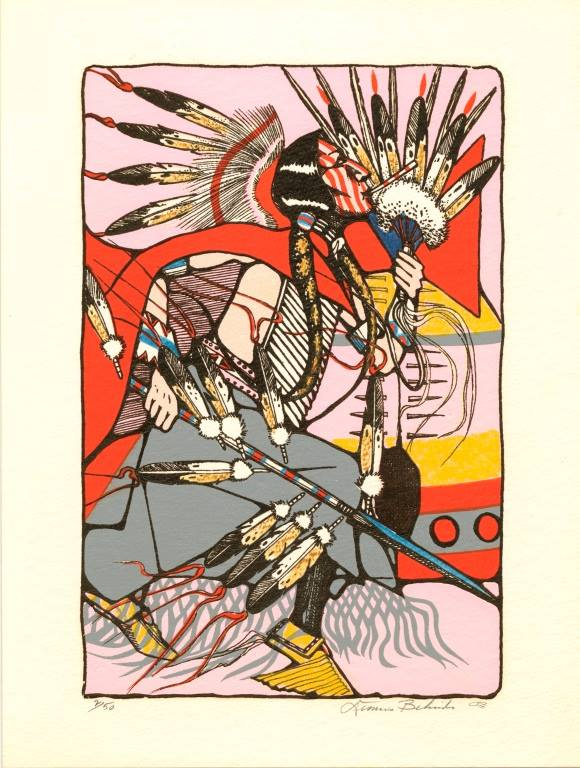

Beginning in early March, Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art will open an exhibition that will feature Dennis's "Kiowa Blackleggins'". The museum holds 11 works by Dennis in their permanent collection, and viewing can be scheduled by appointment. In the Bizzell Memorial Library, a piece by Dennis is on public display. Two pieces of Dennis's work, Eagle Dance (1979) and Black leg Society Dancers (1979), are located in the Art Collection space at the Sam Noble Museum. The Art Collection space is accessible by appointment.