OKLAHOMA CITY, OKLA. – Wastewater surveillance, an early detection tool that pinpointed clusters and surges of COVID-19 infections during the pandemic, continues its relevance in Oklahoma, but with a different focus: monitoring for foodborne pathogens. In the past several months, the University of Oklahoma Wastewater Surveillance Team has published papers about ongoing research and the potential it holds for decreasing the burden of gastrointestinal disease, especially for vulnerable populations.

Because people infected with pathogens shed them in their waste before they develop symptoms of disease, testing samples of wastewater via treatment facilities or manholes provides a window into the gastrointestinal problems that will occur in about a week’s time. The OU team monitors for four foodborne pathogens: Salmonella, Campylobacter, Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) and Norovirus. They are among the most common foodborne pathogens in Oklahoma and typically cause nausea, vomiting, stomach cramps and diarrhea.

The team detailed its discoveries in a study published in the journal Microorganisms. Importantly, the detected pathogens corresponded with the timing of cases that were officially reported to health departments across the state, including their seasonal patterns and peaks. In addition, the team found signs of outbreaks that had been reported in other states but not in Oklahoma, as well as some cases that were never reported anywhere.

“This study was important because it showed us that wastewater surveillance works for foodborne pathogens,” said infectious disease epidemiologist Katrin Kuhn, Ph.D., an associate professor in the Hudson College of Public Health at OU Health Sciences and lead author of the study. “I’ve been working with these pathogens for about 20 years, and I feel like we’re a few steps closer to having accurate, real-time surveillance that can be applied directly to public health.”

The significance of wastewater surveillance is that it accomplishes what traditional surveillance usually cannot. When people become nauseous and have diarrhea, for example, they often don’t go to the doctor, instead waiting until the symptoms go away on their own. That means a pathogen was never confirmed with a lab test, and no report was made to a health department. Even if a person seeks medical help, the doctor may not always order a lab test.

“Through traditional, or passive, surveillance, a whole chain of events has to take place in order for us to know about infections,” Kuhn said. “In some of my previous research, we estimated that for every person who seeks medical attention, receives a diagnosis, and their infection is reported, there could be as many as 200 people who have the same infection, but it never gets reported.”

Kuhn said wastewater surveillance appears to detect signs of an outbreak one to two weeks before people start having symptoms. Knowing about the presence of foodborne pathogens earlier is especially important for more vulnerable populations. Nausea, vomiting and diarrhea can lead to dehydration and other issues, which takes a toll on people in nursing homes or those struggling with another medical condition. Even though the pathogens typically run their course in healthy people, they often miss work because of symptoms, which ultimately has an economic effect.

“Our eventual goal is to be able to let a community know that a pathogen is peaking so they can be extra careful with their hygiene and go to the doctor if they have signs of an upset stomach for more than a few days,” Kuhn said.

Salmonella, Campylobacter and STEC are primarily spread by consuming undercooked meats and by handling food, Kuhn said. If someone cuts raw chicken on a cutting board, slices tomatoes on the board without washing it, and then eats the tomatoes without cooking them, Salmonella or Campylobacter could be transmitted. Sometimes the pathogens are spread outdoors during a muddy bicycle race, for example, where a person unintentionally swallows water or mud containing the microorganisms. Norovirus is spread through bad hygiene — if one person who is infected doesn’t wash his hands after using the bathroom and then prepares food or touches a surface, people who eat the food or touch the same surface face a high risk of infection.

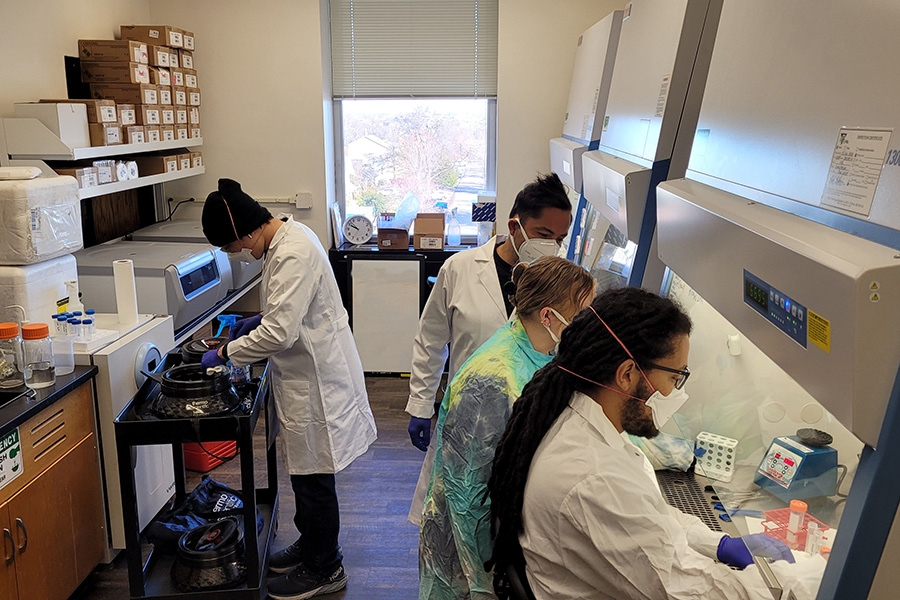

The OU Wastewater Surveillance Team is thought to be among the first in the world to regularly monitor for foodborne pathogens, as opposed to doing it on an episodic basis, Kuhn said. In addition to public health leaders from the OU Health Sciences campus, a team from the Oklahoma Water Survey on the OU-Norman campus leads the collection and analysis of wastewater samples. They work in collaboration with the Oklahoma State Department of Health, the Oklahoma City-County Health Department, the Tulsa Health Department, and other health departments around the state.

Jason Vogel, Ph.D., of the OU School of Civil Engineering and Environmental Science on OU’s Norman campus and director of the Oklahoma Water Survey, said the sampling process that was established for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, has been easily adapted to foodborne pathogens.

“By collecting composite samples over a 24-hour period, our results are representative of the population served by the utilities in that community, which is essential for the analytical results to be applicable to the local population,” Vogel said. “The scientists in the Oklahoma Water Survey Microbiology Laboratory continue to be on the cutting edge of method development for wastewater monitoring of emerging infectious diseases at the community scale.”

The Oklahoma Wastewater Surveillance team is part of the global Wastewater Surveillance for SARS-CoV-2 and Emerging Public Health Threats Research Coordination Network, which recently published a paper on current challenges and future goals in surveillance in the journal Applied and Environmental Microbiology. The Oklahoma team previously contributed to a commentary in the journal Nature Medicine and a study in The Lancet Global Health

About the Project

Funding and support for wastewater surveillance has been provided by the Presbyterian Health Foundation in Oklahoma City, the Oklahoma City-County Health Department, the Tulsa Health Department, Rockefeller Foundation, and the Oklahoma State Department of Health.

About the University of Oklahoma

Founded in 1890, the University of Oklahoma is a public research university located in Norman, Oklahoma. As the state’s flagship university, OU serves the educational, cultural, economic and health care needs of the state, region and nation. OU was named the state’s highest-ranking university in U.S. News & World Report’s most recent Best Colleges list. For more information about the university, visit ou.edu.